Construction Cost Estimation Background and Purpose

Construction cost estimating is the process of forecasting the cost of building a physical structure. Of course, builders and clients both worry about the financial impact of cost overruns and failing to complete a project. That’s why they devote time and effort to estimating how much a project will cost before deciding to move forward with it. Clients considering large projects often seek multiple cost estimates, including those prepared by contractors and those calculated by independent estimators.

Project owners use cost estimates to determine a project’s scope and feasibility and to allocate budgets. Contractors use them when deciding whether to bid on a project. You usually prepare estimates with the input of architects and engineers to ensure that a project meets financial feasibility and scope requirements.

A good cost estimate prevents the builder from losing money and helps the customer avoid overpaying. It’s a core component of earned value management, a project management technique that tracks a project’s performance against the total time and cost estimate.

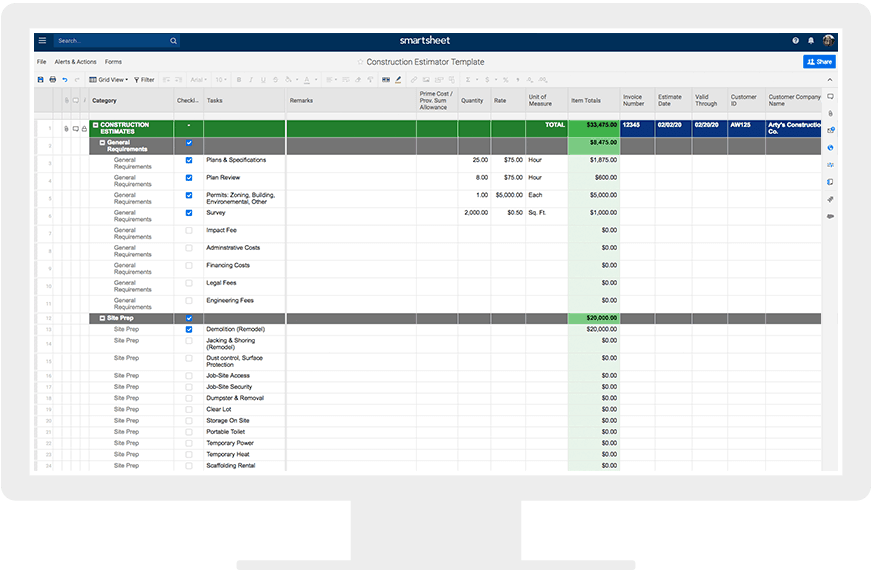

A good starting point is this construction estimator template.

Download Construction Estimator Template

Excel | Word | PDF | Smartsheet

Creating a construction cost estimate is good practice for anyone who cares about how much their project will cost. You routinely do cost estimates for all kinds of construction projects, from building new structures to remodeling.

Accurate estimates are especially critical for development projects, which have budgets and timelines closely linked to paying back lenders and generating revenue as early as possible. They are also essential for large civil projects or mega-projects because of their sizable scope and the potential involvement of public money. On a mega-project, small miscalculations become magnified. In projects constructed with public funds, cost estimates increase accountability, provide transparency, and enhance trust in your ability to manage the project properly.

Failing to prepare a reliable cost estimate can have disastrous results. One notorious example was the Marble Hill nuclear power plant in Indiana. The owner abandoned construction in 1984, seven years after it began. The Public Service Company of Indiana had completed the project only halfway and spent $2.5 billion due to cost overruns.

Estimating the cost of any project with absolute precision is impossible, and projects can fail for unforeseen reasons. But a skilled estimator will account for as many factors as necessary — including such things as market conditions — to create an accurate estimate.

The accuracy of a cost estimate relies on a number of things: the quality of the project plan; the level to which the estimator defines a project; the experience and skill of the estimator; the accuracy of cost information; and the quality of any tools and procedures the estimator uses.

Depending on the type and size of a project, as well as the industry, cost estimation may fall to one individual or a team, and estimators may hold a number of different positions. For some construction projects, contractors and subcontractors prepare the cost estimates, though this is not regarded as best practice. At other times, the construction salesperson will be responsible for creating an estimate. Architectural firms may have in-house estimators, typically people who take on the estimator’s function in addition to their primary role. Increasingly, however, qualified independent estimators handle estimates against which one verifies the contractor’s estimates.

For contractors, good cost estimates win jobs. Customers usually select the lowest bid that meets the standards and specifications they set. In a competitive bidding situation, the time and effort you spend preparing the estimate are a cost of doing business and an investment in winning the job. If urgency is a factor for a project, the speed at which you prepare a bid can also be a differentiator.

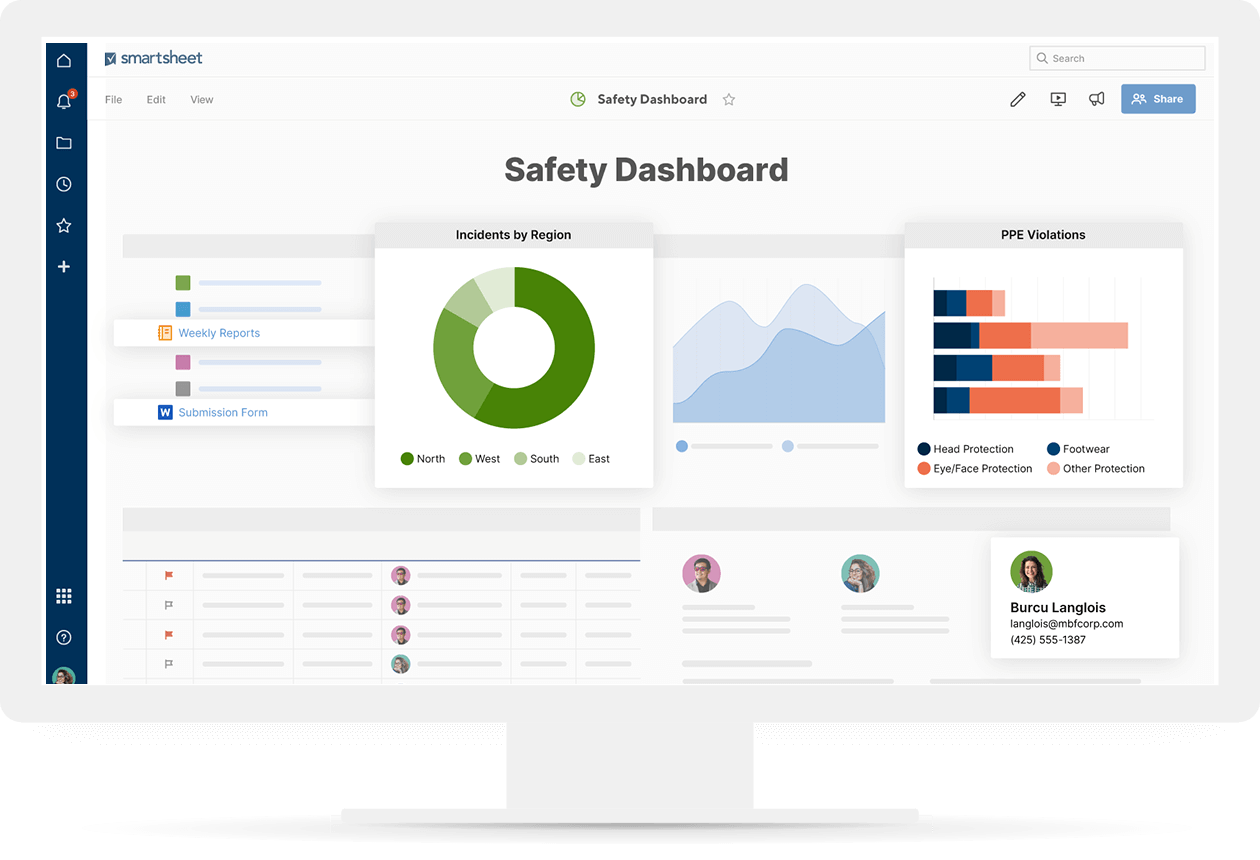

Streamline the construction project lifecycle with Smartsheet

Would you like to manage your construction projects more efficiently, get better visibility into project risks and dependencies, and optimize resource planning?

Smartsheet empowers construction teams to improve visibility to critical information, boost collaboration across field and office teams, and increase overall efficiency, so you can deliver projects on time and on budget.

Transform construction management with Smartsheet. See for yourself.

Smartsheet enables you to track each project with its own dedicated project sheet and get a unified view across all projects in a dashboard. Monitor tasks across projects and capture on-site issues through a simple form on desktop or mobile.

Overview of the Construction Estimation Process

Understanding cost estimation requires you to have a basic grasp of the construction process. (If you’re interested in learning more about the construction process, Pearson’s Building Construction: Principles, Materials, and Systems is an excellent resource.) Here are the nine basic phases of a building project:

1. Commissioning a Project: Commissioning is essentially a verification process that ensures a builder designs, constructs, and delivers a project according to the owner’s requirements. It begins early in the construction process and can last until up to a year of occupancy or use. A commissioning provider carries out commissioning, usually a firm with experience in commissioning buildings that serve particular functions.

2. Determining Requirements: The first real step in constructing a project is a pre-design phase or planning phase. The pre-design phase involves defining a project’s requirements: what its function(s) will be, how much it should cost, where it will be located, and any legal requirements it must comply with.

3. Forming a Design Team: The project owner contracts with an architect who will then select other specialized consultants to form a design team. Complex projects and projects which require meeting specific design requirements — such as acoustics or housing hazardous materials — will have more specialized consultants on board to ensure the design meets requirements. The architect is generally responsible for overseeing and coordinating the design process, though for some projects (such as industrial construction), an engineer may be one of the people overseeing design.

4. Designing the Structure: This step deals with the architect creating a series of designs. The architect works first with the owner to decide on the broad strokes of the design and then increasingly closely with the other members of the design team to flesh out the structure’s design in accordance with requirements. Designing thus progresses from a schematic design phase, when the architect presents a high-level design to the owner for approval, to a design development phase, when the architect works with the design consultants to decide on specifics of the construction design. The last step is the construction documents phase, i.e., creating construction drawings and specifications from which the contractor will build. The specifications, which various participants in the construction process read, appear in a standard format called the MasterFormat, which the Construction Specifications Institute developed. Estimators produce and revise cost estimates for the project as the architect fleshes out the design.

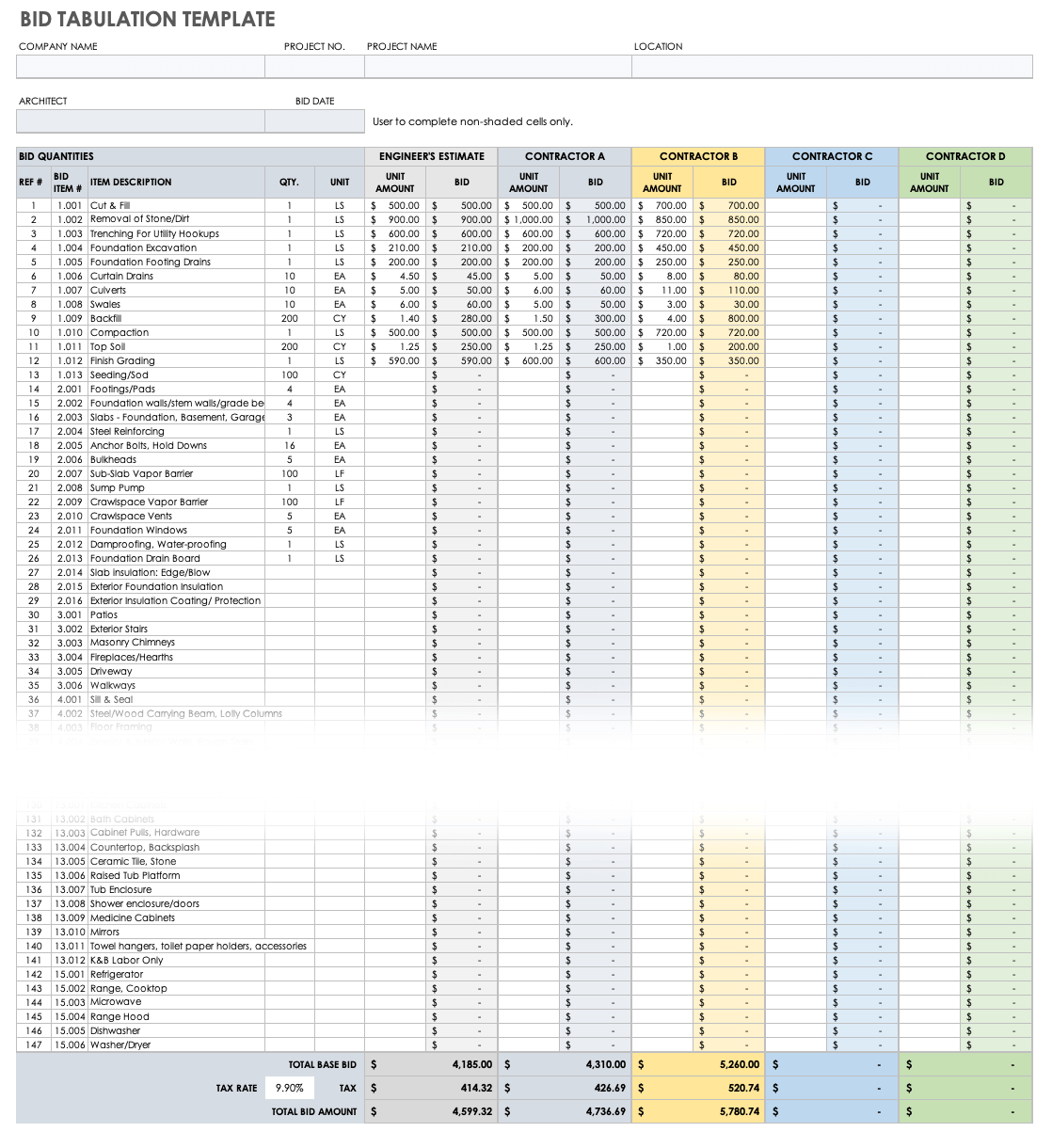

5. Bidding Based on the Scope of Work: Once the construction documents are finalized, they are released to contractors who wish to bid on the project. Along with these bidding documents, they include instructions on how to submit bids, a sample of the contract agreement, and financial and technical requirements for contractors. These documents, which effectively define the scope of the work, are the basis on which contractors prepare their estimates. For more on how to develop a statement of work, consult this guide. To ensure fair bidding, all contractors receive the same information, and the project owner usually selects the lowest qualified bidder. This bid tabulation template can help you compile your estimate.

Download Bid Tabulation Template

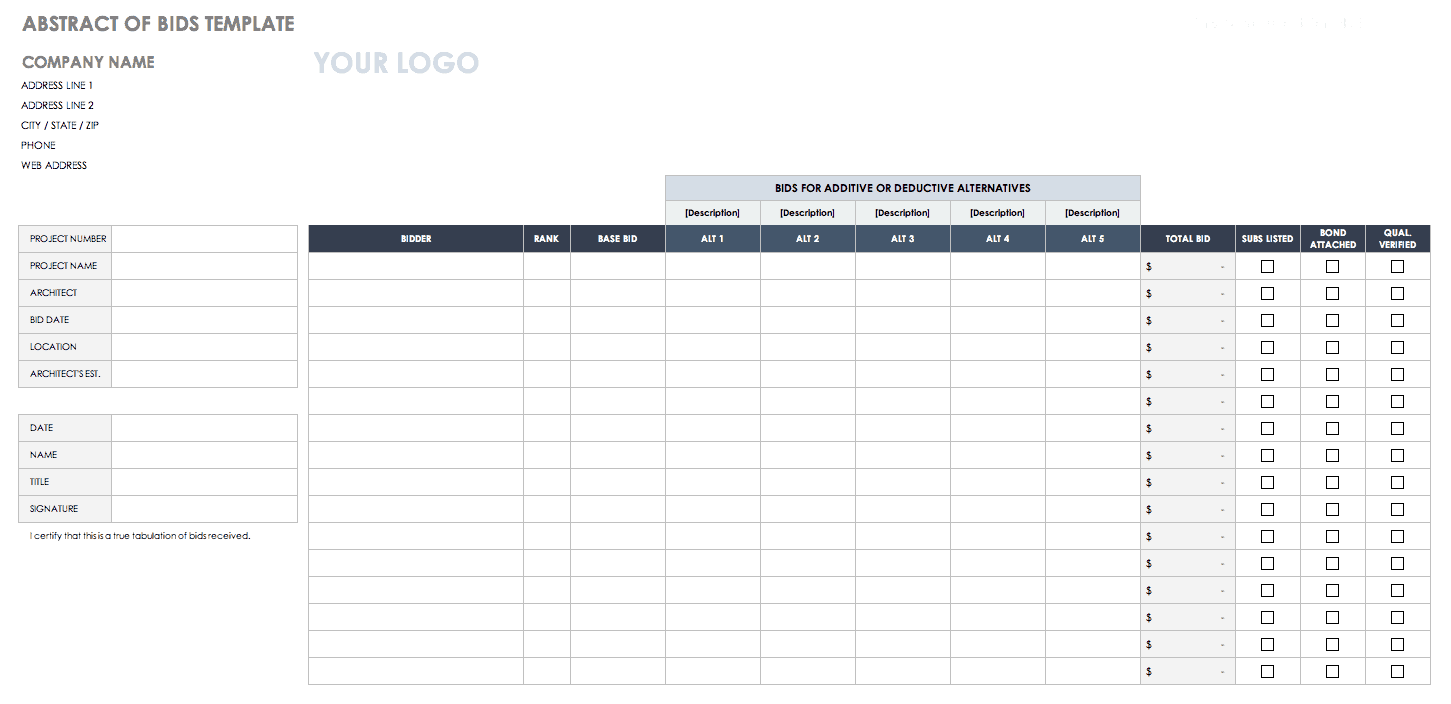

Download Abstract of Bids Template

6. Signing the Contract: Once the contractor has been selected, they execute a set of contract documents with the owner. The contract documents encompass the bidding documents, which now function as a legal contract between owner and contractor. Contracts can follow a number of models, depending on how complete the construction design is and how the owner and contractor bear risks. One of the basic models is a lump sum (also called a stipulated sum or turnkey) contract, which involves the contractor bidding a fixed sum for the total project and agreeing upon it when the project’s design is virtually complete. A unit price contract allows for more flexibility in design by having the owner pay the contractor per number of units they build. A cost-plus contract, signed when the design is incomplete, has the owner pay for all costs plus a predetermined fee for the contractor. A variation of this is cost plus a fee with a guaranteed maximum.

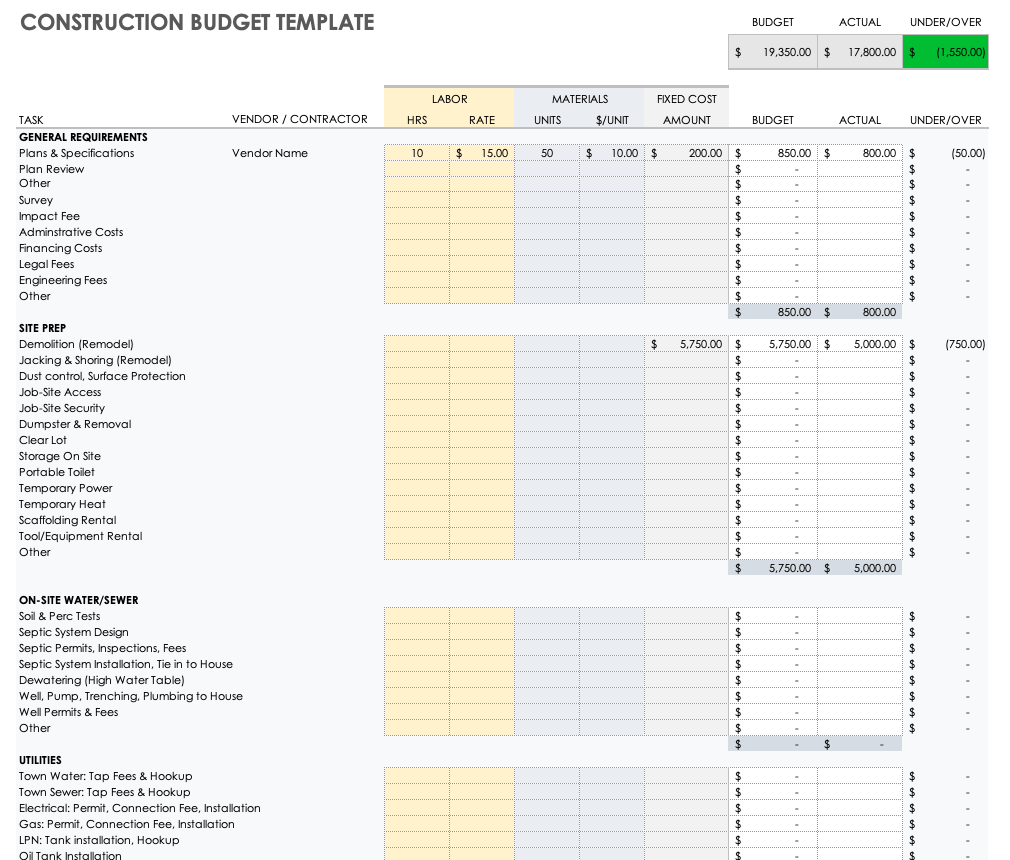

7. Construction: During the construction phase, the contractor oversees building in accordance with the construction documents. A general contractor will hire specialized subcontractors for different sets of construction tasks, such as plumbing or foundation work. Throughout the construction process, the contractor engages in careful cost control, comparing actual expenditure with forecasted expenditure at multiple points in the construction process. Cost control ensures that the contractor is actually able to turn a profit. This budget template can help you compare actual costs to estimated costs.

Download Construction Budget Template

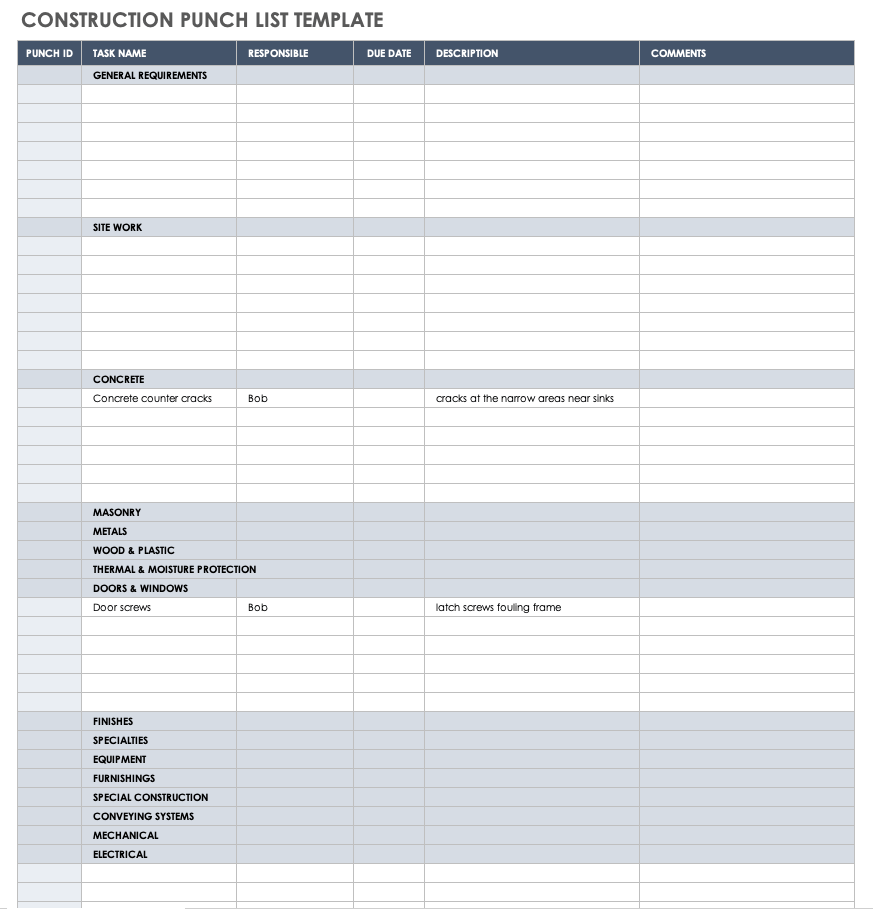

8. Close-Out: When the builder comes close to finishing a structure, the contractor requests the architect perform a substantial completion inspection in which the architect verifies the near-complete status of the project. At this stage, the contractor provides the architect with a document called the punch list, which lists any incomplete work or needed corrections. After the architect inspects the structure, they will add any additional incomplete items to the punch list.

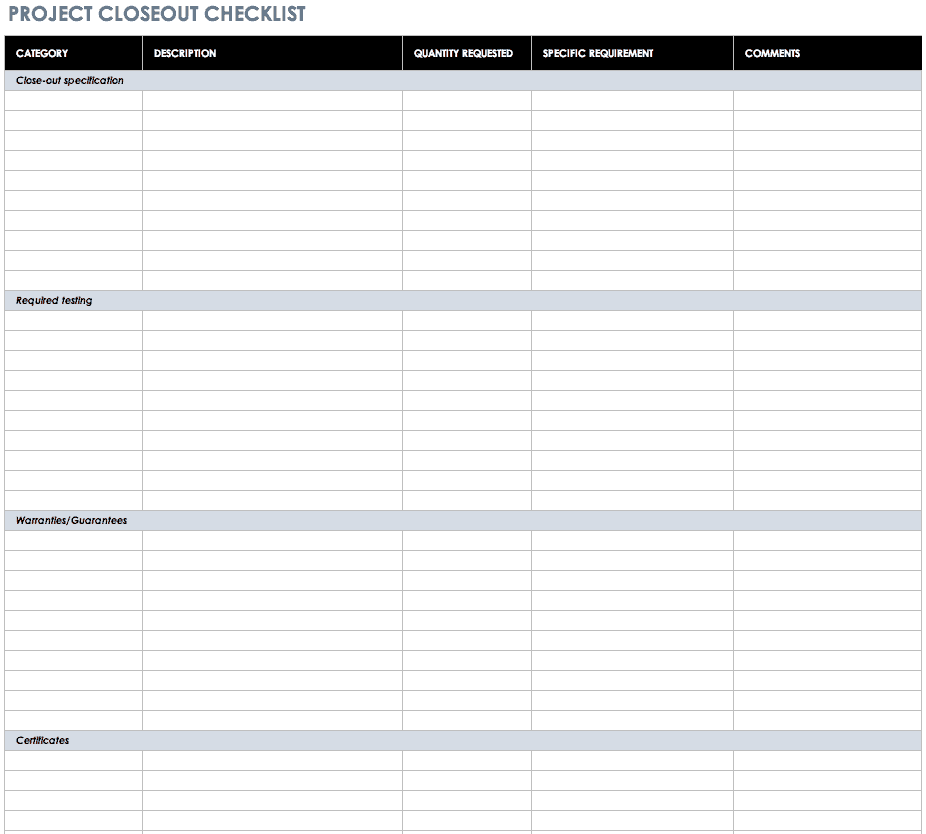

Consult these templates for a project close-out checklist and punch-list template.

Download Construction Punch List Template

Download Project Closeout Checklist Template

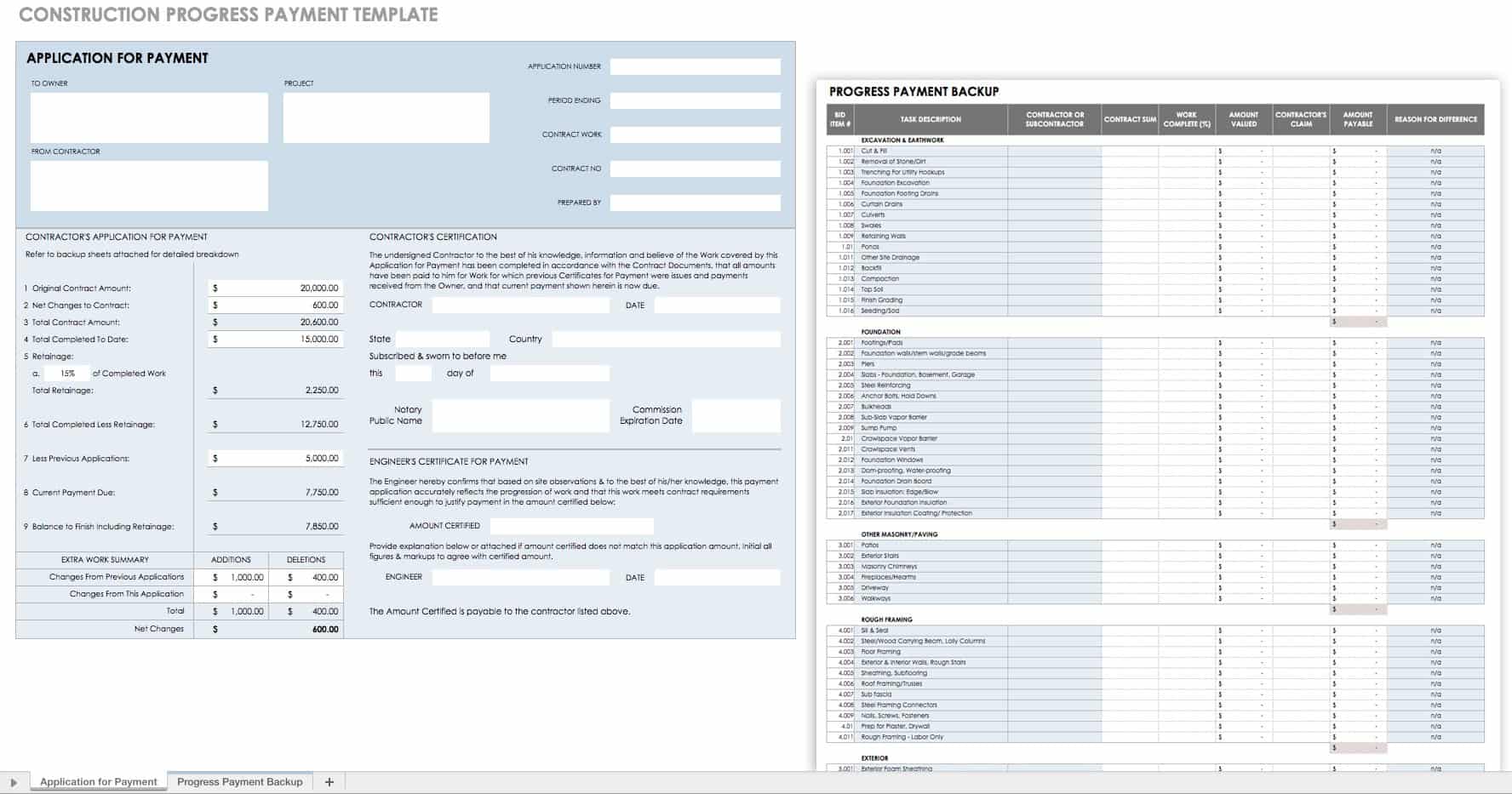

This template will help you keep track of contractor progress payments.

Download Contractor Progress Payment Template

9. Completion: After the contractor completes all the incomplete work detailed on the punch list, the architect performs a final inspection. If the contractor has completed the structure according to construction drawings and specifications, the architect will issue a certificate of final completion, and the contractor is entitled to receive the full payment.

An alternative method of project delivery is the design-build process, which integrates building design and building construction. Instead of contracting first with a design team and then with a contractor, the owner contracts with a design-build firm, which handles both functions. The main strength of this approach is greater alignment and coordination between design and construction and a reduction of construction missteps. Accountability rests with a single party, which owners may appreciate. It can also save time and increase efficiency, and design-build processes are likely to be significantly cheaper than conventional design-bid-construct processes like the one detailed above.

The Main Types of Construction Cost Estimates

Since a cost estimate can only be accurate with a well-defined project plan, it’s standard practice to create multiple estimates during the pre-design and design phases. These become more accurate as the project’s level of definition increases. The American Society of Professional Estimators classifies estimates according to a five-level system that becomes increasingly more detailed and reliable. (Construction cost estimating has a lot in common with cost estimating for other types of projects, and you can read more about key concepts and tips in this article.)

- Level 1: Order of Magnitude Estimate: Made when project design has not yet gotten under way, you only use an order of magnitude estimate to determine the overall feasibility of a construction.

- Level 2: Schematic Design Estimate: An estimate produced in line with schematic design

- Level 3: Design Development Estimate: An estimate made during the design development phase

- Level 4: Construction Document Estimate: An estimate based on the construction drawings and specifications

- Level 5: Bid Estimate: An estimate prepared by the contractor, based on construction documents. The bid estimate is the basis of the bid price offered to the customer.

A simpler system of classifying estimates features just three primary categories: design estimates, bid estimates, and control estimates. These category names reflect the way in which you use the estimates.

- Design Estimates: These estimates, prepared during a project’s pre-design and design phases, start with an order of magnitude estimate, or screening estimate, which determines which construction methods and types are most feasible. Next comes the preliminary estimate, or conceptual estimate, which you base on the schematic design. Then comes the detailed estimate, or definitive estimate, which you base on design development. The last of the design estimates is the engineer’s estimate, which you base on the construction documents. A simple template can help give an initial assessment of costs involved in a project.

Download Constructor Estimator Template

- Bid Estimates: Contractors prepare bid estimates when bidding to construct the project. Contractors will draw from a number of data points to prepare their estimates, including direct costs, supervision costs, subcontractor quotes, and quantity take-offs. (We’ll look at these in more detail shortly.)

- Control Estimates: Prepared after one signs a contractor agreement and before construction gets under way, the control estimate functions as a baseline by which you assess and control actual construction costs. The control estimate also allows contractors to plan ahead to meet upcoming costs and determine the project’s cost to completion.

A Construction Cost Estimates Perspective on Building Systems

Creating a cost estimate for a project as complicated as a building calls for a systematic way of enumerating costs. To simplify the process, cost estimators may use the Uniformat system of viewing a building as a set of seven functional divisions. These are:

- Substructure

- Shell

- Interiors

- Services

- Equipment and furnishings

- Special construction

- Building site work

The RSMeans Square Foot Costs Book, which compiles building cost data according to these divisions, is a widely used resource for developing cost estimates based on costs per square foot.

Contractors who are bidding for a job will create a document called the bill of quantities, which is an itemized list of the work and materials required for a construction project. This is a crucial step in determining the cost of the work before bidding. Creating a bill of quantities is a four-step process that used to be done painstakingly by hand on paper and is now usually done with spreadsheets or specialized software.

- Taking-Off Quantities: Working from the construction documents, a quantity surveyor will measure the tasks and items of work in a project. This requires scaling dimensions from drawings. One will record these in standard units such as area, volume, or length. For example, you can quantify excavation in cubic meters and steel supports in linear feet. It’s important to follow one of the standard methodologies, such as the New Rules of Measurement. The surveyor will list the number of each item in the project.

- Squaring: Next, the quantity surveyor multiplies the dimensions of the component into square area and multiplies this by the number of times this work item occurs in the construction, thus getting the total dimensions, length, volume, and area as applicable.

- Abstracting: Abstracting is the collecting and ordering of the squared dimensions. Similar tasks and components are grouped together. Once you have taken off and squared all items and have obtained total dimensions, they must be merged. You make deductions for any voids or openings in the building, such as stairs.

- Billing: This last step simply involves presenting item descriptions and quantities in a structured format, the bill of quantities. You usually present these in a hierarchy for group, subgroup, and work section. (Examples include substructure, earthwork, and site clearance.)

The Elements of a Construction Cost Estimate

So what information do estimators use to create an estimate? The following are key terms and concepts, but be aware that there’s a large degree of overlap between some of them.

- Quantity Take-Off: Developed during the pre-construction phase, a quantity take-off measures the materials and labor needed to complete a project.

- Labor Hour: The labor hour, or man hour, is a unit of work that measures the output of one person working for one hour.

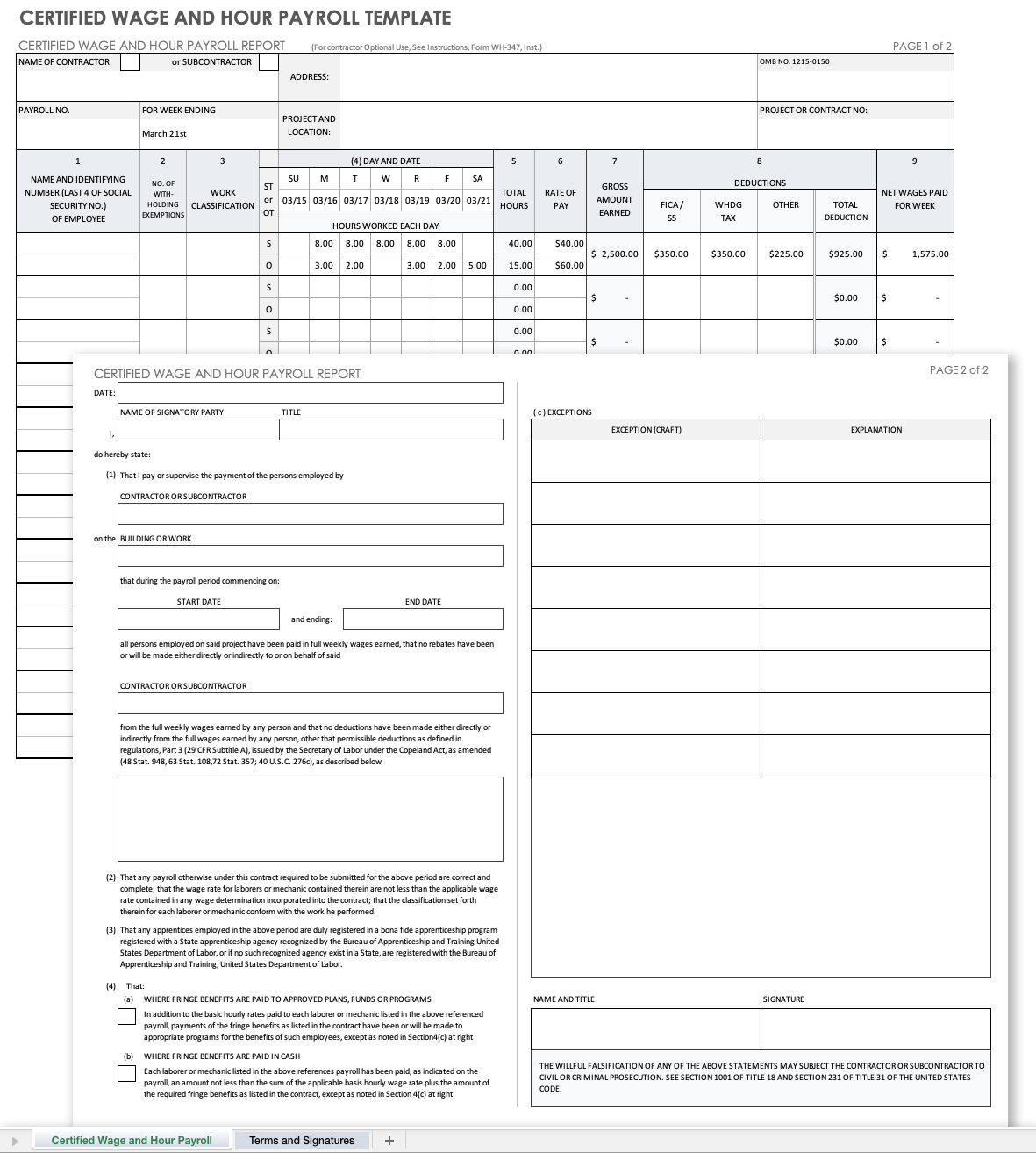

- Labor Rate: The labor rate is the amount per hour one pays to skilled craftsmen. This includes not just the basic hourly rate and benefits, but the added costs of overtime and payroll burdens, such as worker compensation and unemployment insurance. This template will help you keep track of wages and labor hours.

Download Certified Wage and Hour Payroll

Excel | PDF | Smartsheet

- Material Prices: Since the cost of materials is prone to fluctuation based on market conditions and such factors as seasonal variations, cost estimators may look at historical cost data and the various phases of the buying cycle when calculating expected material prices.

- Equipment Costs: Equipment costs refer primarily to the cost of running, and possibly renting, heavy machinery, such as cement mixers and cranes. It’s important to note that the equipment in use influences how quickly you can complete the project, so the use of equipment actually impacts many costs outside of those directly associated with running the equipment.

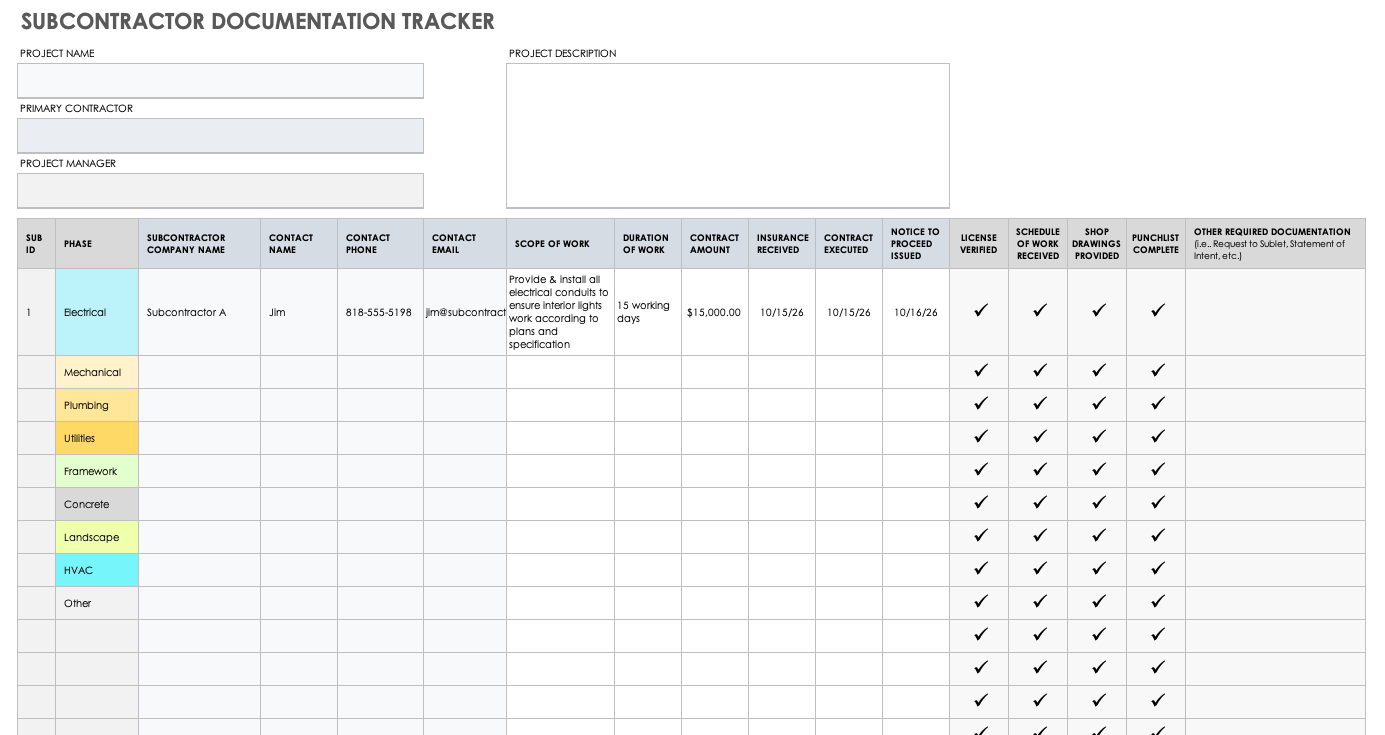

- Subcontractor Quotes: Most contractors will hire multiple specialist subcontractors to complete parts of the construction. You add these subcontractors’ quotes to the contractor’s total estimate. (It can be helpful to use a tracker to collect all the subcontractor documentation in one place.

Subcontractor Documentation Tracker

- Indirect Costs: Indirect costs are expenses not directly associated with construction work, like administrative costs, transport costs, smaller types of equipment, temporary structures, design fees, legal fees, permits, and any number of other costs, depending on the particular project.

- Profits: Of course, in order to make a profit, the contractor adds a margin on to the cost of completing the work. Subcontractors do the same when preparing their own quotes.

- Contingencies: Since even the most accurate estimate is likely to be affected by unforeseeable factors, such as materials wastage, an estimate will usually have a predetermined sum of money built in to account for such added costs.

- Escalation: Escalation refers to the natural inflation of costs over time, and it’s especially vital to take into account for long-running projects. Some projects have escalation clauses that address how to handle this inflation.

- Bonds: An owner will usually require a contractor to arrange for the issuance of a performance bond in favor of the project owner. The bond functions as a kind of guarantee of delivery. Should the contractor fail to complete the project according to the terms of the contract, the owner is entitled to compensation for monetary losses up to the amount covered by the performance bond.

- Capital Costs: Capital costs are simply the costs associated with establishing a facility. These include the following: the cost of acquiring land; the cost of conducting feasibility studies and the pre-design phase; paying the architect, engineer, and specialist members of the design team; the total cost of construction, which covers not just materials, equipment, and labor, but also administrative, permitting, and supervision costs, as well as any insurance fees or taxes; the cost of any temporary equipment or structures that are not part of the final construction; the cost of hiring a commissioner; and the cost of inspecting the structure when it’s near completion.

- Operations and Maintenance Costs: More a concern for the owner than the contractor, one accounts for operations and maintenance costs during the design phase. Making choices that lower the total lifetime cost of a building may result in higher construction costs. Operating costs include land rent, the salaries of permanent operations staff, maintenance costs, renovation expenses (as needed), utilities, and insurance.

- Variances: Owners will often allocate construction budgets that are larger than cost estimates because even good, thorough cost estimates have a tendency to underestimate actual construction costs. This can happen for a number of reasons. For example, wage increases, which can be difficult to forecast, will make construction costs rise. Seasonal or natural events, such as heavy rainfall, may call for action to protect construction or restore the construction site. Large projects in urban areas may face regulatory or legal issues, such as a demand for additional permitting. And lastly, owners who begin construction without finalizing the project’s design will over-budget to account for design changes and the inevitable cost increases that result from throwing a project off schedule.

The Effects of Scale on Construction Cost Estimates

Cost estimators keep one important phenomenon in mind when estimating quantities: costs are not always directly proportional to the size of a facility or the number of units one’s building. If plotted on a graph, this phenomenon, known as an economy or diseconomy of scale depending on which way the cost varies, would appear as a non-linear relationship between facility size and costs.

If the average cost per unit falls as the number of units increases, we have an economy of scale. If the average cost rises as the number of units increases, we have a diseconomy of scale.

The cost exponent is an indicator of whether a scale economy or diseconomy exists. For a discussion of how to calculate cost exponents in construction, consult Project Management for Construction. If the exponent is greater than zero but less than one, an economy of scale exists. If it is greater than one, a diseconomy of scale exists. If it is equal to one, the cost-capacity relationship is unaffected by scale.

You can determine cost exponents using historical data from construction projects of the same type. Once calculated, you can use cost exponents to adjust future cost estimates depending on the scale of a project.

The Major Approaches to Construction Cost Estimation

Cost estimators rely on a number of estimation techniques, which vary in speed and potential accuracy. The major approaches to cost estimating include:

- Production Function: A production function relates the amount built (the output) to factors such as materials and labor (the input). So if you want to achieve a certain level of output (number of square feet built), you look for the optimal input (labor hours per square foot). Production functions can be quite accurate for forecasting input-output relationships for projects of a particular type, and there is extensive data to draw from for certain project types, like schools and hospitals, for example.

- Stick Estimating: Highly accurate, but incredibly time consuming, stick estimating is the practice of determining total costs by listing, in order, the costs for every single component of a job. The sheer amount of time it takes to produce a stick estimate invites errors due to loss of concentration or carelessness.

- Empirical Cost Inference: This statistical method uses regression analyses to relate the cost of construction to a model of predictors. The accuracy of this method depends on the quality of the predictive model, so it calls for a good degree of familiarity with individual predictors of total construction costs and a knowledge of statistical methods.

- Unit Cost Estimating: Unit cost estimating simply associates unit costs with each assembly involved in a construction process. It’s fairly quick and accurate, especially if one has used the assemblies previously, and there is evidence to justify the unit costs for each assembly.

- Allocation of Joint Costs: You allocate costs that are difficult to assign to individual project elements by using different mathematical formulas. For example, you can prorate field supervision proportionally to tasks based on their share of the total basic costs.

The Construction Cost Estimator’s Job

Of course, the cost estimator is central to the cost estimation process. Typically a professional who is familiar with both design and construction and skilled at navigating the myriad costs associated with construction projects, the cost estimator must have both skill and training.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics says there were 213,500 cost estimators in the country in 2014, with employment opportunities expected to grow by nine percent over the next decade. A plurality of these estimators work in the construction industry.

Essential skills for cost estimators include the ability to work quickly with numbers, an in-depth knowledge of construction, and familiarity with construction documents. On large projects, multiple specialist cost estimators may be responsible for estimating different aspects of the project, so a specialization or first-hand experience in constructing certain types of structures can also be valuable.

Although tertiary education is typically a requirement for cost estimators, first-hand experience with construction and a knowledge of the contracting landscape are perhaps more essential skills. Some estimators are individuals who have risen through the ranks as construction workers. These experienced construction professionals also know how to negotiate with subcontractors and may be better able to appreciate the factors that impact estimated amounts.

But as construction has gotten more specialized, professionally trained cost estimators are increasingly common. A number of qualifications in cost estimation are available, including the International Cost Estimating and Analysis Association’s Certified Cost Estimator/Analyst program,the American Society of Professional Estimators’ Certified Professional Estimator certification, and the American Association of Cost Engineers’ certifications for cost consultants, cost engineers, and cost technicians. Most certification programs require continuing education and recertification.

Dedication to continued learning is necessary for all cost estimators, whether certified or not. It’s key to keep abreast of the construction industry and also to be able to learn and implement evolving cost estimation methods and software, which we’ll talk about shortly.

In addition, cost estimators must be highly organized and highly attentive to detail. They should know how to communicate cost information with accuracy and integrity. Moreover, given the competitive nature of the construction industry, they must maintain confidentiality when communicating with stakeholders and commit themselves ethically to delivering accurate estimates despite possible pressures to engage in corner-cutting and expediency.

Best Practices in Construction Cost Estimating and What Not to Do

Today, software applications make cost estimation easier, but the cost estimator’s role remains as crucial as ever. Some best practices can lead to more accurate estimates and more successful bids.

The cost estimator must follow industry norms and standards for measurement units. He must also consistently fill out costing-related documents, such as quantity surveys, and follow cost-recording procedures in a way that makes their work verifiable and easy to handoff to another cost estimator if necessary. The best way to do this is in a recognized construction classification system, such as the UniFormat.

Identifying indirect costs is another key part of the cost estimator’s job, and it’s to some extent a skill developed through experience. The estimator examines contractual terms to see which of them may impact indirect costs. They’re also responsible for calculating indirect costs and for coming up with a way to record these. Determining the level of effort — project work that cannot be traced to specific components of a work breakdown structure — is also a skill that takes some developing. Estimating the labor hours necessary for completing project tasks affects the size of the workforce, workers’ wages, and insurance.

The estimator is responsible for evaluating subcontractors’ bids, particularly taking into account the subcontractors’ performance on past projects. They will review construction drawings for constructability and accuracy in representing the project scope. They will assess how the client’s schedule requirements impact the performance of the project. Their job may involve analyzing completed estimates for accuracy.

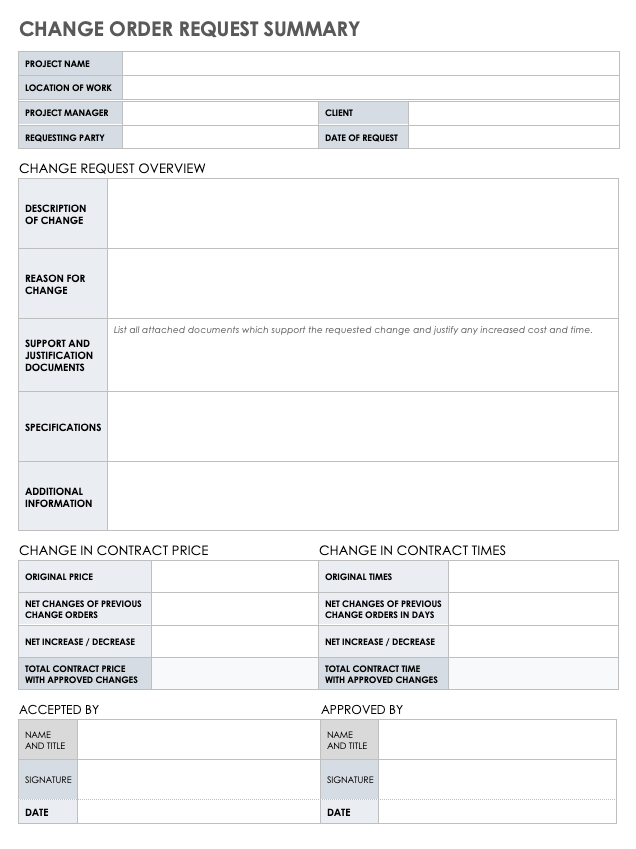

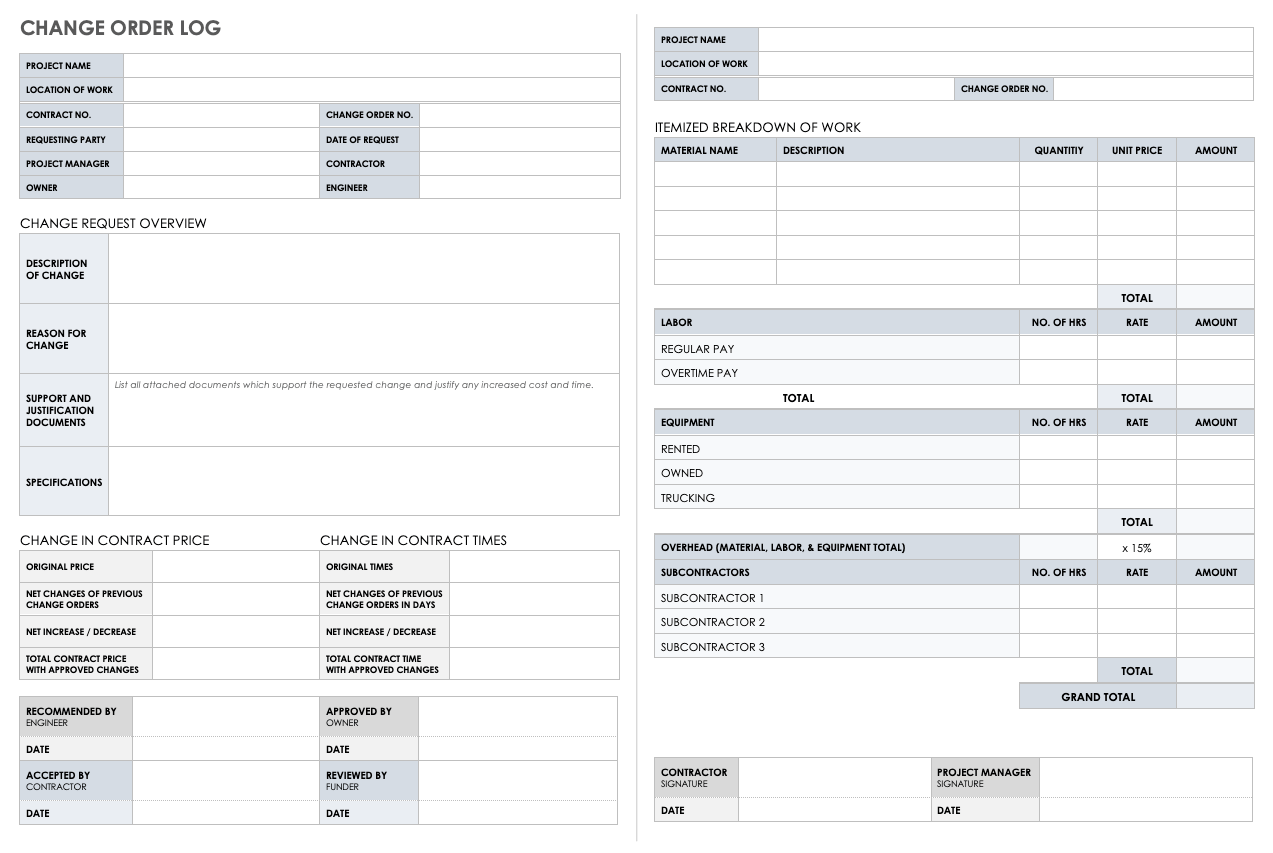

The cost estimator also helps track costs in the field so as to allow the comparison of actual costs with cost estimates. The idea is to see which areas of the estimate were accurate, which weren’t, and why. They’re also responsible for determining the impact of change orders, so contractors and clients can determine if these are feasible. A skilled estimator will provide as much detail as possible on the impact of change orders.

Download Project Change Order Request Form

Ultimately, the cost estimator may have to exercise specialized skills, such as value engineering, which usually refers to increasing the function-to-cost ratio. Value engineering is usually a separate study, and it’s critical to structure an estimate so you can swap out costs and assess the effect of value engineering. If you don’t allocate costs to construction divisions in a format that’s easy to understand, gauging the impact of value engineering can become much more difficult.

Common Pitfalls for Construction Cost Estimators

Experienced cost estimators say you can often avoid common pitfalls by consistently following standard procedures. One common source of problems is the failure to read the project documents carefully, which frequently leads to a poor understanding of the project scope and certain associated costs. Others include forgetting to incorporate costs or entering costs incorrectly. These issues can be compounded by neglecting to thoroughly check the completed estimate.

Other oversights include the failure to visit the site and the inability to fully understand the site conditions. As we talked about earlier, a site’s natural conditions and location can impact costs in a number of ways, and a cost estimator will develop an eye for spotting and asking about these. This makes site visits imperative.

Finally, some cost estimators who draw from cost data repositories will fail to adjust costs based on local conditions or will make arbitrary adjustments without considering prior experience or quantitative comparisons. Either of these can throw estimates off and make it more difficult for another cost estimator to verify an estimate.

Cost Estimating Applications and Software

Estimating applications make cost estimates faster and easier to produce, which is crucial in a construction market that’s immensely competitive. They’re also more accurate than human estimators working on their own, as long as you use up-to-date cost data. Estimation software has become a must-have for anyone generating complex construction cost estimates.

Free cost estimating software is available, but it has limited functionality, and it’s not really suitable for anything but smaller projects. For-purchase software, which can be pricey, is a much better option for anyone dealing with complex projects because of the functionality and features it can offer. Here are a few of the benefits of for-purchase software:

- Cost-Related Inputs and Processes: Estimating software can offer access to cost databases, calculate taxes and the costs of labor and materials, allow estimators to adjust prices to local contexts, feature standard-size room lists, as well as item or activity lists, and integrate with accounting software. Some offer worksheets for specific trades and calculators for standard costs.

- Generating Estimates: Estimating software can perform measurements and take-offs, count objects, allow estimators to mark up construction drawings, and generate bills of quantities.

- Documentation: Estimating software offers templates for proposals and cover letters, generates proposals and cost reports, and maintains records of past projects.

- Other Features: Some software offers support for macros, online collaboration, and the ability to integrate with computer-aided design files.

New Aspects of Construction Cost Estimating

Construction cost estimating continues to evolve as design, building methods, and materials change. Some trends that impact cost estimating today include:

- Building Information Modeling (BIM): A building information model is a digital model of a structure and all its characteristics and dimensions. From the design to the construction, commissioning, and maintenance of a building, all participants can use the model. As such, there’s an increasing demand for cost estimating to become an aspect of BIM, though this opinion has not been without challenges. The main criticism of cost estimating in BIM is that cost estimators, with some justification, have less confidence in the level of detail of BIM designs. That lack of specificity can lead to substantial inefficiencies and reworking of estimates.

- Sustainability and LEED Certification: Currently something of a hot topic in construction, LEED certification is a point system for rating buildings based on their environmental performance. The role of an estimator in projects seeking to obtain LEED certification involves both calculating the cost of scoring LEED points and communicating these to clients. These include not just direct costs (using environmentally friendly materials, for example), but also increased administrative costs for ensuring compliance with the LEED standards. Therefore, estimators in LEED projects should be involved during the construction design phase, so they can contribute information about costs associated with specific LEED points.

- Lean Construction and Cost Control: Lean construction, a fairly new approach, draws from the principles of lean management, which is the systematic effort to reduce waste without affecting productivity. Studies indicate that applying lean principles in construction projects results in significant cost savings. As such, an understanding of lean principles is a good asset for cost engineers who apply principles of value engineering to construction projects.

Further Resources for Learning about Construction Cost Estimating

The following are additional resources concerning construction cost estimating:

- Ibrahim Odeh’s Coursera course on “Construction Cost Estimating and Cost Control” is a popular introductory resource for construction management professionals.

- The Project Management Institute (PMI) offers articles on project estimating.

- The Society of Cost Estimating and Analysis offers a glossary of cost-estimating related terms.

- The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors hosts a variety of knowledge resource events for quantity surveyors, as does the International Cost Engineering Council.

- The Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering International holds an annual meeting that addresses new issues in cost engineering.

Smartsheet Helps You Manage Cost Estimates and Construction Projects with One Tool

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.